RESEARCH REPORT

|

|

Access the article online: https://kjponline.com/index.php/kjp/article/view/469 doi:10.30834/KJP.37.2.2024.469. Received on:18/10/2024 Accepted on: 11/12/2024 Web Published:13 /12/2024 |

FACTORS INFLUENCING RELAPSE AMONG ALCOHOL DEPENDENT PATIENTS- A MIXED METHOD STUDY

Chikku Mathew1*, Nithin K Raju 2, Ambily Nadaraj3

- Consultant Psychiatrist 3. Biostatistician, Caritas Hospital and Institute of Health Sciences, Kottayam

- Assistant Professor, Department of Anatomy, Pushpagiri Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Thiruvalla

*Corresponding Author: Consultant Psychiatrist , Caritas Hospital and Institute of Health Sciences, Kottayam

Email: drchikkuthulamattathil@gmail.com

INTRODUCTION

Substance use disorders tend to recur and are chronic.1 The prevalence of Alcohol use disorder (AUD) has been decreasing in the Americas, Europe, and the Western Pacific.2 However, there is an increasing trend in the prevalence of AUD in Southeast Asia, Eastern Mediterranean, and African regions.2 This is a disorder that results in high morbidity and mortality, causing 2.6 million deaths per year.2 Research proves that treating this condition during the withdrawal phase is an easy task with successful results; however, preventing relapse is a trickier situation that is far more challenging than the initial treatment.3,4 Relapse is one of the important barriers to rehabilitation. The majority of alcohol-dependent patients relapse within a year, with the first three months being the most critical period5. Despite the availability of treatment, 85% of treated alcohol dependent patients relapse, even after long periods of abstinence.6 In particular, the first three months post-treatment encompasses the period of greatest vulnerability, and more than half of patients will lapse within 2 weeks.6

Relapse is a complicated and intricate process governed by many neurobiological and psychosocial factors.7-9 In cutting-edge research by Marlatt et al. 10, 11 relapse has been defined as an unfolding process that appears to be determined by many internal and external stressors, with reinstitution of substance use

bringing the final blow. Mattoo et al. state that a plethora of factors like adverse emotional conditions, interpersonal issues, and social beliefs mixed with low self-efficacy and helplessness leads to lapses into substance use. This eventually culminates into a full relapse.12 Most research works on alcohol relapse have suggested a multi-factorial etiology behind relapse, with a complex interaction between neurobiological, psychosocial, and environmental factors playing a key role. Thorough research into identifying risk factors for alcohol relapse is of utmost importance to formulate relapse prevention strategies.

Studies have revealed that factors such as older age, poor literacy, unemployment, nuclear family, family history, early initiation, longer duration of abuse, and undesirable events are associated with relapse. However, internal factors like withdrawal symptoms (81.3%), inability to control urges (8%), and boredom or frustration (6.6%) also contribute to relapse.13 Alcohol use disorder is a chronic and disabling condition involving many cycles of treatment and relapse. Studies claim that the chronicity of the condition is worsened in the presence of another Psychiatric disorder.14 Additionally, factors such as craving, poor motivation, peer pressure, and stressful life events also contribute to relapse.1 Alcohol use disorder patients with high self-efficacy, who rely on approach and less on avoidance coping, who have a good social network and have positive life events tend to stay abstinent. 13

Despite the abundance of literature on factors associated with relapse in Alcohol Use Disorders, very few studies have tried to ascertain the patient-related factors associated with relapse using qualitative methods. This mixed method study uses qualitative methodology to elucidate patient-related factors related to relapse and quantitative methods to ascertain whether factors such as the presence of Psychiatric disorders, Severity of craving, Levels of motivation, and Severity of dependence contribute to relapse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study has followed a mixed method – concurrent parallel design. The study was initiated with the objectives of eliciting the occurrence of psychiatric co-morbidities, severity of alcohol dependence, craving, and motivation among alcohol relapsers. The study also ascertains factors associated with relapse through in-depth interviews (IDI) and focus group discussions (FGD). For the purpose of this study, relapse is defined as a return to drinking at least after two weeks of abstinence, characterized by the usage of more than five standard drinks for at least five or more days. Participants were patients with a diagnosis of Alcohol dependence syndrome (ADS) attending the Psychiatry inpatient and outpatient units of a General Hospital after relapse. Only those alcohol dependent patients (aged between 20 years to 60 years) with a history of relapse who gave consent to participate in the study were included. Those patients with a general medical condition that does not permit them to respond to a structured questionnaire or that affected their ability to understand the nature of the study and follow or partake in the interview process were excluded from the study. Participants who presented with intoxication or delirium were recruited only after the resolution of these issues. The study began in the month of July 2023 and was concluded by March 2024. The study commenced after receiving ethical clearance from the Caritas Hospital and Institute of Medical Science. (CH/EC/NOV2023/02)

By considering the proportion of Alcohol Dependence Syndrome to be 16.3% (absolute precision of 8 with 95% CI), 82 subjects were recruited consecutively after obtaining informed written consent.15 Sample size of the qualitative part depended on the redundancy of information. The socio-demographic data was collected through a semi-structured Performa. Mini-International neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I) was used to diagnose psychiatric co-morbidities.16 The Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS), a five-item scale with a cut-off score of 20, was used for the assessment of craving.17 The Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SADQ) is a 20-item questionnaire designed to measure the severity of dependence. A score of 31 or higher indicates severe alcohol dependence.18 The Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES) was used to assess motivation. The instrument yields three scores: Recognition (Re), Ambivalence (Am), and Taking Steps (Ts).19 SOCRATES total scores, Re, Am, and Ts, were categorized as very low, low, medium, high, and very high based on the decile scores from the SOCRATES alcohol profile sheet.

The qualitative phase of the study aimed to identify factors associated with relapse. The tools were an IDI guide and a FGD guide. Six IDIs and five FGDs (each with 6-8 participants) were held concurrently. IDIs were done among both inpatients and outpatients, and FGDs were done among inpatients. All discussions and interviews were held in Malayalam, a native Indian language, and lasted for about 15-20 minutes. After establishing the rapport, the sessions commenced with the principal investigator urging the participants to respond to questions from a structured guide. The investigator remained neutral and flexible throughout the sessions. All the sessions were conducted by the principal investigator. All the sessions were audio recorded, data was then transcribed and translated into English.

Quantitative analysis: All Descriptive Statistics were expressed as Mean ± SD for continuous variables and number and percentage for categorical variables. The association between the PACS score, SADQ Score, and SOCRATES was determined using the Chi-Square test. All analyses used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS software, IBM Inc, New York, USA) version 26.

Qualitative analysis was done using the RQDA software using grounded theory methodology. The narrative material was imported into RQDA, and units related to the aim of the study were identified from the material. Subsequently, codes were added, and RQDA’s code reports were used to determine the frequency of each code. Text searches were also used to identify specific text passages relevant to the research questions. Finally, the coded data was exported as HTML files; the codes were then clustered into sub-themes and themes. A total of thirty-three codes were grouped under four themes. The investigators corroborated these individually to avoid bias.

RESULTS

Quantitative phase

Data collected from 82 participants revealed the mean age to be 44.45. Most of the participants were employed (84.1%), married (82.9%) and college graduates (54.9%). The majority resided in urban areas (62%). Participants started to use alcohol at a mean age of 21 years. The mean age at dependence was found to be 31 years. An average period of 10 years was obtained as the years of alcohol dependence. (Table 1)

Table 1: Socio-demographic Profile

|

Religion |

Christian |

45 (54.9%) |

|

Hindu |

37 (45.1%) |

|

|

Marital status |

Married |

68 (82.9%) |

|

Unmarried |

9 (11.0%) |

|

|

Divorced |

5 (6.1%) |

|

|

Education |

<5th |

5 (6.1%) |

|

5 - 12th |

32 (39.0%) |

|

|

Degree |

45 (54.9%) |

|

|

Employment |

Yes |

69 (84.1%) |

|

No |

13 (15.9%) |

|

|

Socio-economic status |

APL |

72 (87.8%) |

|

BPL |

10(12.2%) |

The majority of the participants had mild physical dependency (47.6%), 37.8 % had moderate dependency, and 14.6 % had severe alcohol dependency. The mean PACS score obtained was 11.84(11.84+_ 5.71), with 91.5 % of the sample obtaining scores below 20. About 41.5 % had a medium level of motivation, 43.9% had a high degree of motivation, and 14.6% had a very high degree of motivation. Half of the sample had recognized problems regarding their drinking, and 6.1 % had medium recognition scores. More than 50 % of the participants were ambivalent about their alcohol use, reflecting that they were contemplating making a change in their drinking. 29.3 % of the participants reported that they were taking steps to make a change in their alcohol use. (Table 2)

Table 2: SADQ, PACS, and SOCRATES scores

|

Scale |

Score |

|

SADQ |

18 ± 11 |

|

Mild Dependency |

39 (47.6%) |

|

Moderate Dependency |

31 (37.8%) |

|

Severe Alcohol Dependence |

12 (14.6%) |

|

Socrates Total |

74 ±14 |

|

Less than 70 (Up to Medium) |

34 (41.5 %) |

|

71 – 90 (High) |

36 (43.9 %) |

|

Above 90 (Very high) |

12 (14.6 %) |

|

Socrates RE |

26.16 ± 5.05 |

|

7 – 26 (Very Low) |

41 (50.0) |

|

27 – 30 (Low) |

28 (34.1) |

|

31 – 33 (Medium) |

5 (6.1) |

|

34 – 35 (High) |

8 (9.8) |

|

Socrates AM |

14.88± 3.83 |

|

4 – 8 (Very Low) |

6 (7.3) |

|

9 – 13 (Low) |

23 (28.0) |

|

14 – 15 (Medium) |

9 (11.0) |

|

16 – 17 (High) |

22 (26.8) |

|

18 – 20 (Very High) |

22 (26.8) |

|

Socrates TS |

32.76 ± 5.59 |

|

8 – 25 (Very Low) |

5 (6.1) |

|

26 – 30 (Low) |

22 (26.8) |

|

31 – 33 (Medium) |

21 (25.6) |

|

34 – 36 (High) |

10 (12.2) |

|

37 – 40 (Very High) |

24 (29.3) |

|

PACS Score |

11.84 ± 5.71 |

|

Nil craving |

75 (91.5 %) |

|

Craving + |

7 (8.5 %) |

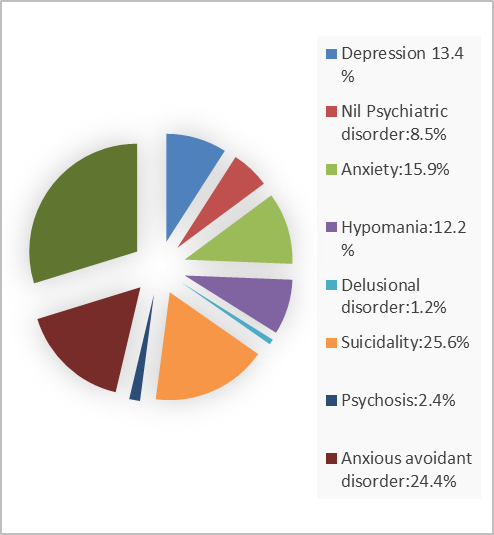

The majority of the population had co-morbid psychiatric disorders (91.5%). In this category, emotionally unstable personality disorder was the most common, with a prevalence of 43.9%. 53.7 % of the sample had tobacco dependence, and 4.9% of the sample had cannabis dependence. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Proportion of Psychiatric disorders

A significant association was obtained between the severity of dependence and craving. No participants with mild alcohol dependency had craving as per PACS Score (p=0.016). The majority of participants with a medium or high level of motivation to quit had no craving for alcohol; there was no statistically significant association between craving and levels of motivation (p=0.063). (Table 3) Furthermore, the study could not find a significant association between psychiatric disorders and the severity of dependence/motivation levels/ craving.

Table 3: Relationship between severity of dependence and craving, levels of motivation, and craving for alcohol

|

|

Nil craving (75) |

Craving + (7) |

P value |

|

|

SADQ |

Mild Dependency (n=39) |

39 (100.0) |

0 |

0.016 |

|

Moderate Dependency (n=31) |

25 (80.6) |

6 (19.4) |

||

|

Severe Dependence(n=12) |

11 (91.7) |

1 (8.3) |

||

|

SOCRATES |

Less than 70 (Medium) (n=34) |

33 (97.1) |

1 (2.9) |

0.063 |

|

71 – 90 (High) (n=36) |

30 (83.3) |

6 (16.7) |

||

|

Above 90 (Very high) (n=12) |

12 (100.0) |

0 |

||

Qualitative phase

The opening statement used for both interviews and focus group discussions was regarding the topic and purpose of the interview/ discussion. Central Questions aimed at finding about the periods of alcohol use, periods of sobriety, and periods of relapse. The concluding questions were aimed at obtaining any further information from the participants. Qualitative analysis of the transcribed data revealed the following four categories: 1) Drinking Motives, 2) Self Perception, 3) Misconceptions related to alcohol use, and 4) Social factors. Participants disclosed the most common factor behind relapse to be peer pressure followed by misconceptions regarding alcohol use.

Theme 1: Drinking Motives

Drinking motives refer to the factors that motivate patients to drink. Two sub-themes of internal and external motives were identified.

The external motives related to relapse were identified as peer pressure, family issues, and financial stressors.

Having alcohol enabled the participants to enjoy the camaraderie in their respective peer groups. “Whenever I go with friends for a tour, I always need to drink. They don’t compel me, but I feel good and happy when I drink with them” (FGD 4) brings out the underpinnings of using alcohol as a group. One of the participants in his late sixties quotes connoted that alcohol use is something that assures the quality of life after retirement: “I have an élite circle of friends; in this circle, all of us do use alcohol. I don’t find what’s wrong with it. Being by the riverside, with my friends, gossiping and chit-chatting with a glass of alcohol is something I had always wished for” (IDI2).

Some of the participants believed that family members didn’t understand their issues, and they felt that they needed to drink to cope with these issues. Some also had issues pertaining to unruly children and extramarital affairs, leading to relapse. Some thought that they needed alcohol to take up familial responsibilities. “My father met with an unexpected death, making me responsible for the entire family. I can’t deal with this burden” (FGD 5). “At times, my family nags me, and thus I go and drink to make them angry. I believe that if they are angry, they won’t talk much. I drink to shut them out” (FGD2).

Relapsing to deal with financial stressors was one other core issue that was talked about. “I have so many financial debts. This is the main reason why I drink. I am very worried thinking about it; alcohol calms me down” (FGD3).

Internal motives to relapse back were identified as follows.

Some patients relapse due to withdrawal issues, sleeplessness, and tiredness that occur as the aftermath of alcohol abstinence. “I get tremors early in the morning. So, I drink to control it. I also have sleep issues; alcohol helps me sleep better” (FGD3).

“I am also very afraid of having tremors. Others might notice it. Therefore, I drink a bit before leaving for work. I feel more confident when there is a bit of alcohol in me” (IDI6). For some of them, craving and impulsivity were the major reasons to relapse. “Craving for alcohol is that sole factor which prompts me to drink. When I see others drink, I am not able to control myself” (FGD3). (Table 4)

Table 4: Theme: Drinking Motives

|

THEME |

SUB-THEME |

CODES |

DATA EXTRACT |

|

DRINKING MOTIVES |

EXTERNAL MOTIVES |

PEER PRESSURE |

“Whenever I go with friends for a tour, I always need to drink. They don’t compel me, but I feel good and happy when I drink with them” (FGD4) |

|

FAMILY ISSUES |

“My father met with an unexpected death, making me responsible for the entire family. I can’t deal with this burden” (FGD 5) |

||

|

FINANCIAL STRESSORS |

“I have so many financial debts. This is the main reason why I drink. I am very worried thinking about it; alcohol calms me down” (FGD3).

|

||

|

INTERNAL MOTIVES |

WITHDRAWAL SYMPTOMS |

“I get tremors early in the morning. So, I drink to control it. I also have sleep issues; alcohol helps me sleep better” (FGD3). |

|

|

CRAVING |

“Craving for alcohol is that sole factor which prompts me to drink. When I see others drink, I am not able to control myself” (FGD3). |

Theme 2: Self-perception

The second theme identified was self-perception, which conceptualizes the participant’s perception of their internal values and mood states, which results in relapse. For some of the patients, alcohol use was a coping mechanism to deal with negative mood states or stress. “I get emotional very soon. At times to control my anger or sadness, I drink” (FGD2). “I am extremely anxious. Alcohol helps me face others and deal with my stress” (FGD5). Some of them also expressed the idea of alcohol use being a reward or reinforcement to their happy states “After coming back from work, I don’t have anything else to do, so alcohol is a pleasure-seeking activity” (FGD1). “I have had counseling sessions before, but no one has ever understood the fact that alcohol makes me happy. If I abstain, I don’t think so that I can ever be happy and pleasant” (IDI3). “I don’t have anything else that gives me happiness as alcohol does.”(FGD5)

Some patients opined that money-spending habits and alcohol use often interplay and exist together. “I started to earn money at a young age. I would like to do things that I like with my hard-earned money, and alcohol is one among them” (FGD5).

“Though I am spending money, I don’t regret it because the money I spend goes to the government” (IDI1). One of the interviewees expressed that he has reached the stage of stagnation in life and that alcohol use makes him deal with it. “I have worked tirelessly with the Government service for more than thirty years. There is so much I have attained. Now it’s my time to enjoy” (IDI2).

Many opined that they are in control of their use and they can continue their use as it is not problematic. “I have never created issues at home while being drunk. I am a very decent drinker.” (IDI4). Few of the participants expressed that being sober would make them unhappy and intolerant. “If I am sober, I believe that I won’t be able to deal with these problems, and everyone would consider me a loser” (IDI4). (Table 5)

Table 5: Theme: Self Perception

|

THEME |

CODES |

DATA EXTRACT |

|

SELF PERCEPTION |

MOOD STATES |

“I get emotional very soon. At times to control my anger or sadness, I drink” (FGD2). |

|

COPING MECHANISMS |

“I am extremely anxious. Alcohol helps me face others and deal with my stress”(FGD5) |

|

|

REINFORCEMENT |

“After coming back from work, I don’t have anything else to do, so alcohol is a pleasure-seeking activity” (FGD1). |

|

|

MONEY SPENDING HABITS |

“I started to earn money at a young age. I would like to do things that I like with my hard-earned money, and alcohol is one among them”(FGD5). |

|

|

NON PROBLEMATIC USE |

“I have never created issues at home while being drunk. I am a very decent drinker.” (IDI4). |

Theme 3: Misconceptions related to alcohol use

Though the majority of the study participants knew about the harmful side effects of alcohol, they wanted to continue the use because alcohol offered them relief from their health issues. “I also have leg pain and numbness, which eases with alcohol use” (FGD4). During a focus group discussion, one of the participants quoted that alcohol does not cause cancer like tobacco (FGD2), which yet again points out misconceptions regarding alcohol-related health issues.

During an interview, an interviewee brought out, “I have friends who use alcohol on a daily basis; they haven’t had any deaddiction treatments. Therefore, I do not understand why I should get one. I can reduce, but never stop. I am aware that quitting and taking medications for it will create issues; I know my friends who have become mentally ill after stoppage “(IDI 5), which reveals the participant's perception regarding de-addiction treatment. (Table 6)

Table 6: Theme: Misconceptions Related to Alcohol Use

|

THEME |

CODES |

DATA EXTRACT |

|

MISCONCEPTIONS RELATED TO ALCOHOL USE |

MISCONCEPTIONS REGARDING ALCOHOL RELATED HEALTH ISSUES |

“I also have leg pain and numbness, which eases with alcohol use” (FGD4). |

|

MISCONCEPTIONS REGARDING DEADDICTION TREATMENT |

“I am aware that quitting and taking medications for it will create issues, I know my friends who have become mentally ill after stoppage” (IDI 5) |

Theme 4: Social factors

Participants conveyed the idea that alcohol use is legalized and hence is acceptable to use it. “Alcohol isn’t an illegal substance, so I don’t understand the problem in using it” (FGD 5). The fact that alcohol can be bought very easily was another factor leading to relapse. “Alcohol is easily available. Even if I want to stop, there are bars and outlets in every nook and corner” (FGD4). Some of them perceived that the portrayal of alcohol use in media makes them confused about usage. “I am influenced by so many factors like films. When the heroes in the movies use alcohol, I feel it’s ok to take it” (FGD5). Alcohol use during social gatherings was also normalized. “I want to drink during social gatherings and festivities. I love being with my friends and sharing a glass with them” (IDI 5). (Table 7)

Table 7: Theme: Social Factors

|

THEME |

CODES |

DATA EXTRACT |

|

SOCIAL FACTORS |

LEGAL STATUS |

“Alcohol isn’t an illegal substance, so I don’t understand the problem in using it” (FGD 5) |

|

EASY AVAILABILITY |

“Even if I want to stop, there are bars and outlets in every nook and corner” (FGD4). |

|

|

MEDIA INFLUENCE |

“When the heroes in the movies use alcohol, I feel it’s ok to take it” (FGD5) |

|

|

FESTIVITIES |

“I want to drink during social gatherings and festivities.”(IDI 5) |

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is one of the few research works on factors influencing relapse among alcohol dependent patients done using both qualitative and quantitative designs. Data from 82 participants revealed the mean age to be 44.45 years. Research shows that patients over 35 years of age had higher chances of relapse. 20, 21 The majority were employed (84.1%), currently married (82.9%), and graduates (54.9%). The majority resided in urban areas (62%). These results were analogous to the study results by Sau et al.22 These results might also be due to the location of the study center in an urban area. The majority of participants who relapsed had been married, which reflects the influence and role of close ones in initiating de-addiction treatment. Participants started alcohol use at a mean age of 21 years and had been dependent on alcohol for more than 10 years, which is an analogous result obtained in other studies.13, 23

In the current study, 53.7% of the sample had tobacco dependence, similar to other studies.20 Majority had the presence of a psychiatric disorder which is identical to other studies.24 In this category, emotionally unstable personality disorder was the commonest, with a prevalence of 43.9%. Previous research works have also investigated the role of personality traits as predictors of relapse, revealing that patients who were both low in conscientiousness and high in neuroticism had a higher risk of relapsing25. Patients with high emotional instability and behavioral disinhibition showed higher relapse rates.24 In other studies, disorders like bipolar disorder20,25, anxiety disorders20, depression25and antisocial personality disorders25 were commonly associated with alcohol relapse.

Most participants had mild physical dependency (47.6%) in contrast to the study by Kumar et al where the majority had severe dependence.1. The mean score of PACS was 11.84, similar to the study by Rampure et al.13 Less than half of the sample (41.5 %) had only a moderate degree of motivation to quit alcohol use. Studies have found that motivation to change is a deciding factor in alcohol abstinence.23

The qualitative phase of the study revealed four themes: 1) Drinking motives 2) Self-perception, 3) Misconceptions related to alcohol use, and 4) Social factors leading to relapse. These themes have been replicated in other studies as well.26 Participants reported that factors such as peer influence, undertaking familial and financial responsibilities, and withdrawal symptoms were the main reasons behind relapse. In-depth interviews revealed the core issues, physiological and emotional issues resulting in relapse. Focus group discussions could cover the general reasons for relapse, societal influence, and the influence of family related to relapse. Factors such as negative self-image, alcohol withdrawal symptoms, family conflicts, cravings, peer pressure, and family conflicts have been identified in other qualitative studies.27 Qualitative design could bring out the emotional underpinnings leading to relapse.

CONCLUSION

The present study's findings throw light on factors related to relapse into alcohol use. Factors such as co-morbid tobacco use and the presence of borderline personality disorders were higher in patients with relapse. Patients with severe dependence had higher craving for alcohol. Motives related to usage, Self-perception about alcohol use, Misconceptions related to alcohol use, and Social factors leading to relapse were the results from the qualitative phase of the study. This study has certain limitations, such as the study being restricted to a single institution, thus affecting the generalization of the results. The data was collected using self-reported questionnaires, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions, which might have had recall bias issues. Methodologies of proximity triangulation, respondent validation, and deviant case analysis were not used in this study, which might have affected the qualitative arm of the study. Further studies are essential to bring out the underpinnings behind relapse into alcohol use and to formulate a relapse prevention model. More qualitative studies should be done in large population samples, which will aid in bringing out the patient-related factors related to relapse.

REFERENCES

- Kumar P, Thadani A. Prevalence and correlates of relapse in adult male patients with alcohol dependence: a cross-sectional study conducted in a tertiary care hospital in Northern India. Int J Adv Med. 2022 Feb 23; 9(3):229–35. DOI: 10.18203/2349-3933.ijam20220383

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health and treatment of substance use disorders. 2024. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/377960. (Accessed on September 10th)

- Brandon TH, Vidrine JI, Litvin EB. Relapse and Relapse Prevention. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007 Apr 27;3(Volume 3, 2007):257–84. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091455

- Tao YJ, Hu L, He Y, Cao BR, Chen J, Ye YH, et al. A real-world study on clinical predictors of relapse after hospitalized detoxification in a Chinese cohort with alcohol dependence. PeerJ. 2019 Aug 28; 7:e7547. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.7547

- Saunders B, Allsop S. Relapse: A psychological perspective. Br J Addict. 1987; 82(4):417–29. DOI: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01497.x

- Barillot L, Chauvet C, Besnier M, Jaafari N, Solinas M, Chatard A. Effect of environmental enrichment on relapse rates in patients with severe alcohol use disorder: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2023 May 12; 13(5):e069249. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069249

- Stewart J. Psychological and neural mechanisms of relapse. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2008 Jul 18; 363(1507):3147–58. DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0084

- Ciccocioppo R, Hyytia P. The genetic of alcoholism: learning from 50 years of research. Addict Biol. 2006 Sep 1; 11(3–4):193–4. DOI: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00028.x

- Feltenstein MW, See RE. The neurocircuitry of addiction: an overview. Br J Pharmacol. 2008; 154(2):261–74. DOI: 10.1038/bjp.2008.51

- Marlatt GA, George WH. Relapse Prevention: Introduction and Overview of the Model. Br J Addict. 1984; 79(4):261–73. DOI: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1984.tb00274.x

- Larimer ME, Palmer RS, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention. An overview of Marlatt’s cognitive-behavioral model. Alcohol Res Health J Natl Inst Alcohol Abuse Alcohol. 1999; 23(2):151–60. PMCID: PMC6760427

- Mattoo SK, Chakrabarti S, Anjaiah M. Psychosocial factors associated with relapse in men with alcohol or opioid dependence. Indian J Med Res. 2009 Dec; 130(6):702. PMID: 20090130

- Rampure R, Inbaraj LR, Elizabeth CG, Norman G. Factors Contributing to Alcohol Relapse in a Rural Population: Lessons from a Camp-Based De-Addiction Model from Rural Karnataka. Indian J Community Med. 2019 Oct-Dec; 44(4):307-312. DOI: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_321_18

- Sliedrecht W, de Waart R, Witkiewitz K, Roozen HG. Alcohol use disorder relapse factors: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2019 Aug; 278:97-115. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.038

- Acharya M. Depression in Patients with Alcohol Dependence Syndrome in a Tertiary Care Center: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2021 Aug; 59(240):787–90. DOI: 10.31729/jnma.6967

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998; 59 Suppl 20:22-33. PMID: 9881538

- Flannery BA, Volpicelli JR, Pettinati HM. Psychometric Properties of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999; 23(8):1289–95. PMID: 10470970

- Stockwell T, Murphy D, Hodgson R. The Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire: Its Use, Reliability and Validity. Br J Addict. 1983; 78(2):145–55. DOI: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1983.tb05502.x

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Assessing drinkers' motivation for change: the stages of change readiness and treatment eagerness scale (SOCRATES). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006; 10(2): 81–89. DOI:10.1037/0893-164X.10.2.81

- Soman S, Vr A. The prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities and relapses in males treated for alcohol dependence syndrome – Prospective study from tertiary de-addiction care unit in Kerala, India. Eur Psychiatry. 2017 Apr; 41(S1):s879–s879. DOI:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1774

- Nagaich N, Radha S, Neeraj G, Sandeep N, Subhash N. Factors affecting remission and relapse in alcohol dependence can they really predict? J Liver Res Disord Ther. 2016; 2(3);78-81. DOI: 10.15406/jlrdt.2016.02.00028

- Sau M, Mukherjee A, Manna N, Sanyal S. Sociodemographic and substance use correlates of repeated relapse among patients presenting for relapse treatment at an addiction treatment center in Kolkata, India. Afr Health Sci. 2013 Sep 6; 13(3):791–9. DOI: 10.4314/ahs.v13i3.39

- Van Trieu N, Uthis P, Suktrakul S. Alcohol dependence and the psychological factors leading to a relapse: a hospital-based study in Vietnam. J Health Res. 2020 Jan 1; 35(2):118–31. DOI: 10.1108/JHR-07-2019-0157

- Yazıcı AB, Bardakçı MR. Factors Associated with Relapses in Alcohol and Substance Use Disorder. Eurasian J Med. 2023 Dec; 55(1): S75-S81. DOI: 10.5152/eurasianjmed.2023.23335

- Stillman MA, Sutcliff J. Predictors of relapse in alcohol use disorder: Identifying individuals most vulnerable to relapse. Addict Subst Abuse 2020. 1(1): 3-8. DOI: 10.46439/addiction.1.002

- Singh G, Husain Kazmi SS. A Qualitative Study of the Perception of Alcohol Dependence Syndrome Patients and Their Perspective towards Cognitive Therapy. J Adv Res Sci Soc Sci. 2023 Jan 11; 6(1):314–27.DOI: 10.46523/jarssc.06.01.28

- Shorey RC, Stuart GL, Anderson S. Early maladaptive schemas among young adult male substance abusers: A comparison with a non-clinical group. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013 May 1; 44(5):522–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.12.001

Funding: Self funded

Conflict of Interest: None

|

Please cite the article as Chikku M, Nithin KR, Ambili N. Factors Influencing Relapse Among Alcohol Dependent Patients - A Mixed Method Study. Kerala Journal of Psychiatry 2024; 37(2): 109-119. |