COLUMN: TIPS ON RESEARCH AND PUBLICATION

|

|

Access the article online: https://kjponline.com/index.php/kjp/article/view/604 doi:10.30834/KJP.38.2.2025.604 Received on:07/12/2025 Accepted on: 07/01/2026 Web Published:10 /01/2026 |

HOW TO SELECT AND REPORT THE APPROPRIATE STUDY DESIGN

Samir Kumar Praharaj*1, Shahul Ameen2

- Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India 2. Consultant Psychiatrist, St. Thomas Hospital, Changanacherry, Kerala, India

*Corresponding author: Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India.

Email address: samirpsyche@yahoo.co.in

INTRODUCTION

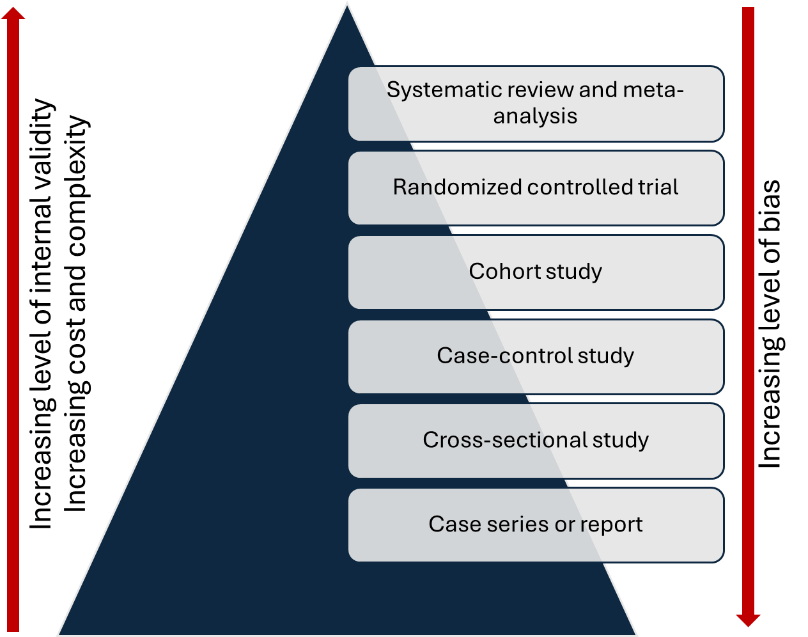

A sound understanding of study designs is an integral part of research methodology training and is essential for planning research. The choice of study design depends on the research question, and more than one design may be appropriate for a given question.1 The study designs can be arranged based on the level of evidence. (Figure 1) Incorrect use of the research design poses a threat to the internal validity of the study (i.e., the findings are not credible due of methodological limitations). In addition, different study designs present distinct challenges to both internal and external validity (i.e., generalizability of the study findings). A thorough understanding of these aspects is crucial for planning a study and for critically evaluating research.

Figure 1: Level of study designs in the evidence pyramid

There is considerable confusion surrounding the terminology used to describe study designs, and errors in reporting them are common, which can mislead readers. A basic understanding of commonly used terms and the key characteristics of each study design can help researchers plan their studies more effectively. Many of these terms are not mutually exclusive and may be used to describe the same study. 2 For this reason, it is better to avoid using such descriptors in manuscripts to prevent confusion and instead describe the study design clearly using the most widely accepted terminologies. (Table 1)

Table 1: Terminologies in study design

|

Qualitative vs quantitative |

Quantitative studies involve numerically collected data that are analysed using statistical tests and may include hypothesis testing. In contrast, qualitative studies involve the analysis of non-numerical data—such as text, audio, video, or images—and are generally used for generating hypotheses. |

|

Clinical vs basic research |

Clinical research typically involves human participants, whereas basic research generally includes experiments conducted on animals or other laboratory-based studies.

|

|

Primary vs secondary |

When investigators collect data themselves and then analyse and publish the results, it is primary data analysis. Such analyses follow the study’s prespecified objectives outlined in the protocol, which is usually registered prospectively in a trial registry. In contrast, when researchers analyse data collected for another study or obtained from an existing database, it is secondary data analysis. This includes situations in which new objectives or hypotheses are formulated after data collection and previously collected data are reanalysed. For example, “Changing profile of suicide methods in India: 2014–2021”3 calculated suicide rates using National Crime Records Bureau data. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are also forms of secondary research. |

|

Observational vs experimental |

In observational studies, researchers ‘observe’ the natural course of a disease, symptom, or behaviour, identify associated risk factors, and evaluate outcomes. The independent variables (called exposures) are not manipulated and are allowed to vary naturally. In contrast, in experimental (or interventional) studies, one ‘intervenes’ to alter the course of a disease, symptom, or behaviour. In these studies, the researcher actively manipulates the independent variables (called interventions) to examine their effects. Such interventions may be preventive or therapeutic. These interventional studies are commonly referred to as clinical trials.

|

|

Prospective vs. retrospective |

Studies can be classified as prospective or retrospective, depending on whether data were collected before or after the study began. Retrospective studies analyse data that were previously collected for another purpose or at an earlier time. Cohort studies can be either prospective (e.g., a study on the incidence of delirium in the paediatric intensive care unit by Sudhakar et al.)4 or retrospective (e.g., a study on the clinical reasons for stopping clozapine by Grover et al.).5 In contrast, case-control studies are always retrospective. Therefore, studies should not be described solely as prospective or retrospective; they should also be identified as either cohort or case–control designs.

|

|

Descriptive vs analytical |

If a study describes the characteristics of a sample without conducting hypothesis testing, it is considered a descriptive study. Descriptive studies commonly report prevalence and summarise other characteristics. For example, Dutt et al. described the phenomenology and treatment of catatonia using only summary statistics, without any hypothesis testing.6 In contrast, analytical studies involve hypothesis testing using statistical methods. They evaluate comparisons between two or more groups or assess associations between variables based on a prespecified hypothesis. |

|

Exploratory vs confirmatory |

A study with prespecified objectives and explicitly stated hypotheses that are formally tested is called a confirmatory study. For example, Chan et al.7 tested the hypothesis that depression was associated with internalised stigma in patients with HIV infection. In contrast, an exploratory study does not begin with predefined hypotheses; instead, multiple statistical tests are conducted to identify potential patterns or relationships in the data. For example, Mahadevan et al. examined the association between several inflammatory markers and psychosis.8 In some studies, exploratory analyses may also be conducted in addition to the primary, prespecified hypothesis-driven analyses. |

|

Comparative vs non-comparative |

A study in which the same outcome measure is assessed across two or more groups is called a comparative study. In contrast, a non-comparative study evaluates outcomes within a single group or examines different outcomes without directly comparing groups. The inclusion of a comparison group in a cross-sectional study makes it a cross-sectional comparative study. |

|

Cross-sectional vs longitudinal |

A study using a single, one-time assessment is a cross-sectional study, whereas a longitudinal study involves repeated assessments.

|

|

Efficacy vs effectiveness |

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that apply strict inclusion criteria to select participants are considered efficacy studies. In contrast, real-world studies with broader inclusion criteria that reflect the characteristics of typical patients are known as effectiveness studies or pragmatic trials.

|

CLASSIFICATION OF STUDY DESIGNS

There are various types of qualitative study designs; however, this manuscript focuses exclusively on quantitative study designs. A useful way to classify studies is by distinguishing between experimental and observational studies, based on whether the investigators assign the interventions. Experimental studies are superior to observational studies because they are less prone to bias; however, they are more difficult to conduct.

EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES

Experimental studies are classified according to the number of study groups and the method of intervention assignment. Studies with a single group are described as pre-post study (also known as a before-after or quasi-experimental designs). Studies with two or more groups are classified as controlled trials. The control group may receive no intervention, a sham (or placebo) intervention, or an active intervention. Controlled trials may be randomised or non-randomised, depending on whether randomisation is used for group assignment. RCTs may follow superiority, non-inferiority, or equivalence designs, depending on whether the aim is to show that the new experimental intervention is superior to, not inferior to, or clinically equivalent to the standard treatment.

Randomisation in experimental studies reduces confounding, making RCTs the gold standard in evidence-based medicine and preferred over non-randomized designs. Allocation concealment (keeping the randomisation sequence hidden from those assigning participants) is an important criterion for assessing the quality of an RCT.

OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES

There are three types of observational studies—cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional—based on their assessment of exposure and outcome, and are ranked here in increasing order of bias (from the most robust to least). All observational studies can be categorised into one of the three types, and it is best to avoid additional descriptors unless necessary. In case-control studies, participants are selected based on their outcome status, whereas in cohort studies, participants are chosen based on their exposure status. For example, in a case-control study that compares patients with depression and matched normal controls for the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACE), the grouping is based on whether depression, which is the outcome, has occurred. In contrast, in a cohort study on a group of people who have experienced childhood adversities and a control group that hasn’t, and keeps monitoring them for the appearance of depression, the inclusion in the groups is based on the exposure, which in this case is ACE.

In a prospective cohort study, individuals with (exposed) or without (unexposed) the exposure are identified and then followed forward in time to observe outcomes, which may be single or multiple. The outcomes have not occurred at the time of recruitment. In contrast, in a retrospective cohort study, the outcomes have already happened at the time the study is initiated. Investigators determine exposure status from existing records (collected before the outcomes occurred) and then assess disease outcomes using those records. Stretching the previous example, if an earlier study had recorded the history of ACE in a group of school students, and a study done six years later had assessed the same group for depressive symptoms, and now the relationship between the two variables is examined in a new study, that would be a retrospective cohort study.

In a case-control study, the researcher identifies cases (individuals with the disease) and controls (individuals without the disease), then looks back in time (i.e., retrospectively) to compare past exposures. When information on both exposure and outcome is collected at a single point in time, the study is termed a cross-sectional study. The distinction between a case-control study and a cross-sectional study is primarily determined by differences in sampling (sampling based on outcome in case-control studies vs. sampling from a population in cross-sectional studies) and directionality (backwards-looking in case-control studies vs. a single-time-point “snapshot” in cross-sectional studies). For example, if we assess a group of college students for a history of ACE and also for depression, this is a cross-sectional study because the information on depression, the outcome, is being collected along with that on the exposure, ACE.

Because data are collected simultaneously in cross-sectional designs, establishing a temporal relationship between exposure and outcome is challenging. However, for certain variables, the temporal order is inherently clear (e.g. ACE and current level of depression in adults). Sometimes, a case-control study is nested within an ongoing cohort study—this is known as a nested case-control study. For example, during the above-mentioned prospective cohort study, if we compare people who have developed depression with matched controls from the same cohort without depression and compare the rates of ACE, which would be a nested case-control study.

Observational studies are more common but are limited by confounding. Confounders are variables that influence both the exposure and the outcome, potentially distorting the observed relationship. For example, in the study of coffee as a risk factor for lung cancer, smoking is a confounder. Hence, identifying potential confounders during study planning is essential to minimise bias. Although not all confounders can be anticipated in advance, every effort should be made to identify and account for them.

WHICH DESIGN TO CHOOSE FOR YOUR STUDY?

One of the most common mistakes made by novice researchers is deciding on a study design prematurely—often before formulating a clear, answerable research question or conducting a thorough literature review to identify gaps in existing knowledge. The choice of study design depends largely on the research question. When the question is clearly articulated, the appropriate study design options become evident. (Table 2). Researchers can then select a design logically—one that best answers the question while also considering available resources. The evidence pyramid serves as a guide to the strength of evidence and can help when choosing among multiple options. As you move up the pyramid, internal validity increases (and bias decreases), but so does the cost and complexity. For example, an RCT is generally preferable to a cohort study when feasible. However, if an RCT is not feasible for ethical reasons, a prospective cohort study is the next best choice. In new areas of research, simpler study designs, such as cross-sectional, case-control, or retrospective cohort studies, may be used. However, to generate robust evidence, prospective cohorts or RCTs may be required.

Table 2: Classes of research questions and the corresponding study designs

|

Research question |

Study design |

|

Incidence/ Prevalence |

Cross-sectional survey, cohort study |

|

Treatment efficacy |

Clinical trial |

|

Treatment harm |

Clinical trial, cohort study, case-control study |

|

Screening |

Clinical trial |

|

Diagnostic Accuracy |

Clinical trial, cross-sectional study |

|

Prognosis |

Clinical trial, cohort study |

|

Etiology |

Cohort study, case-control study |

COMMON ERRORS IN MANUSCRIPTS

- Study design is not mentioned: It is not uncommon to find submitted or even published manuscripts that do not specify the study design. Authors should clearly identify whether the study is experimental or observational. If experimental, specify whether it is randomised or non-randomised; if observational, indicate whether it is a cohort, case–control, or cross-sectional study. Without this essential information—especially when sufficient methodological details are provided—readers may find it difficult to interpret the study’s approach and findings accurately.

- Incorrect reporting: In some manuscripts, the study design is reported incorrectly. For example, case-control studies are sometimes mislabelled as cohort studies, particularly when a retrospective cohort study is mistakenly described as a case–control design. More commonly, cross-sectional studies are mislabelled as case-control studies. In cross-sectional studies, the sample is selected based on neither exposure nor outcome, whereas in case–control studies, participants are chosen based on the outcome. Similarly, reporting a study simply as prospective or retrospective, or exploratory or confirmatory, without providing additional details, can confuse readers. Such misreporting can lead to a misunderstanding of the study’s methodology and validity.

- Inappropriate conclusions: A common mistake in published articles is drawing conclusions about temporal sequence or causality from cross-sectional studies, even though both variables are measured at the same time, and the direction of the relationship cannot be established. Interpretations should generally be restricted to associations unless the causal direction can be clearly inferred from the variables examined and supported by established criteria for causal inference (e.g., biological plausibility).

- Not identifying confounders: This is a common issue in observational research. Failure to identify important confounders can compromise the interpretation of results. For example, in the study of the association of ACE and depression, confounders such as socioeconomic status and parental mental health should not be ignored. Although not all confounders can be anticipated before the study begins, efforts should be made to identify them through a literature search, and appropriate statistical adjustments may be required during analysis.

- Randomisation method: In some studies, participants are allocated in an alternating manner, which does not constitute true randomisation. The process of randomisation—such as computer-generated sequences or the use of a random number table—should be clearly described in the manuscript.

- Allocation concealment: It is often not reported in published manuscripts, raising concerns about the overall quality of the study. The best method of allocation concealment is generally considered to be centralised randomization (via a secure telephone or web-based system). Sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelopes (SNOSE) are acceptable if done meticulously, but human error (e.g., holding envelopes to light or opening them out of order) can compromise concealment.

REPORTING STUDY DESIGNS

It is recommended that the study design be clearly stated for readers early in the manuscript. Typically, the study design is mentioned in the Methods section, often in the opening paragraph. In some cases, it is included alongside the study objectives at the end of the Introduction. Additionally, mentioning the study design in the title of the manuscript is also advisable. Guidelines have been developed to promote proper reporting of different study types (https://www.equator-network.org/).

LAST COMMENTS

Honest reporting of study elements informs readers of the actual study design followed. However, every effort should be made to report the study design correctly and accurately. Consulting a statistician during the study design phase can help prevent major issues, such as peer reviewers or editors identifying an inappropriate study design. Nonetheless, even with careful planning and review, errors may occasionally go unnoticed—only to be identified later by a diligent reader, often through a communication to the editor.

The authors attest that there was no use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) technology in the generation of text, figures, or other informational content of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Praharaj SK, Ameen S. How to choose research topic? Kerala J Psychiatry. 2020; 33(1): 80–84. DOI: 30834/KJP.33.1.2020.188

- Andrade C. Describing research design. Indian J Psychol Med. 2019; 41(2): 201–202. DOI: 4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_66_19

- Arya V, Page A, Vijayakumar L, Onie S, Tapp C, John A, et al. Changing profile of suicide methods in India: 2014-2021. J Affect Disord. 2023; 340: 420–426. DOI: 1016/j.jad.2023.08.010

- Sudhakar G, Aneja J, Gehlawat P, Nebhinani N, Khera D, Singh K. A prospective cohort study of emergence delirium and its clinical correlates in a pediatric intensive care unit in North India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022; 72: 103070. DOI: 1016/j.ajp.2022.103070

- Grover S, Chaurasiya N, Chakrabarti S. Clinician reasons for stopping clozapine: A retrospective cohort study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2023; 43(5): 403–406. DOI: 1097/JCP.0000000000001735

- Dutt A, Grover S, Chakrabarti S, Avasthi A, Kumar S. Phenomenology and treatment of catatonia: A descriptive study from north India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2011; 53(1): 36–40. DOI: 4103/0019-5545.75559

- Chan BT, Pradeep A, Prasad L, Murugesan V, Chandrasekaran E, Kumarasamy N, et al. Association between internalized stigma and depression among HIV-positive persons entering into care in Southern India. J Glob Health. 2017; 7(2): 020403. DOI: 7189/jogh.07.020403

- Mahadevan J, Sundaresh A, Rajkumar RP, Muthuramalingam A, Menon V, Negi VS, et al. An exploratory study of immune markers in acute and transient psychosis. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017; 25: 219–223. DOI: 1016/j.ajp.2016.11.010

SUGGESTED READINGS

- Andrews J, Likis FE. Study design algorithm. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2015; 19: 364–368. DOI: 1097/LGT.0000000000000144

- Cronin P, Rawson JV, Heilbrun ME, Lee JM, Kelly AM, Sanelli PC, et al. How to report a research study. Acad Radiol. 2014; 21(9): 1088–1116. DOI: 1016/j.acra.2014.04.016

|

Please cite the article as: Praharaj SK, Ameen S. How to select and report the appropriate study design. Kerala Journal of Psychiatry 2025; 38(2): 154-60. |